Chapter 1

New Beginnings

On May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew a single-engine Ryan monoplane,

The Spirit of Saint Louis, across the Atlantic Ocean to Paris, France. The lapsed

time was thirty-three and a third hours. I was nine years old.

It was the same year that I retired my cowboy suit and stabled my broom

for a horse in the garage, and declared that I was going to be an aviator.

Instead of playing cowboys and Indians, my playmates and I donned aviator

helmets bought at the Kress Dime Store, and with outstretched arms zoomed

and swooped around the neighborhood, making our version of an airplane’s

engine noise in flight.

Mother, alarmed at my ardent interest in aviation, countered with a plan

of her own. I had shown a mild interest in music, but it was just a small flame

that threatened to be no more than a flicker. Together, my parents conspired

to change the direction of my future. For Christmas that year, I received a

violin, one of Sears Roebuck’s best. I believe it cost nine dollars. For the

world I wouldn’t hurt their feelings, but when they saw me strumming the

violin like a guitar, they knew their son would never play first chair in the

string section in the New York Symphony Orchestra.

Mother was not discouraged. She had offered piano and violin lessons.

They were her favorite instruments, not mine. A few weeks later my dad said

that he was sorry that I had no interest in music “but your mother and I . . .”

I stopped him and said that I did like music, but I had no interest in taking

piano or violin lessons, “those are girls’ instruments!” He asked me what I

would like. “I’m not sure,” I said. “I think that I would like to play a trumpet

or trombone.”

“You’re not big enough to play a trombone,” he said. “I’ll talk with Mr.

Fitch. He runs the Fitch Band School of Music. We’ll have a talk with him

and maybe you can make up your mind.”

A few days later he said, “We have a meeting with Mr. Fitch on Saturday.

I want you to pay close attention to what he says and ask any questions you

may have. It’s a big decision for you to make. Mother doesn’t want another

fiasco like the one we had with the violin.”

“What does ‘fiasco’ mean?” I asked.

“It’s an ignominious failure,” he said.

“What’s ‘ignominious’ mean?” I asked.

“It’s an unexplained failure,” he replied

“Oh?” I said.

“Oh! Look it up!” Dad replied impatiently.

I liked the sound of the word and rattled it around in my mind for a few

days looking for a word to go with “fiasco” to make a sentence. The closest I

could come up with was the word “nuance.” “Fiasco of the nuance” sounds

high tone, but I never found a way to use it. Oh well, I suppose it was an

ignominious failure.

During the summer we built model airplanes of balsa wood and rice paper.

Rubber bands extending from the tail to the nose of the plane connected to

a balsa wood propeller providing the power for them to fly. Mostly they

just crashed, leaving nothing more than a heap of irreparable parts and a

reminder of the two or more weeks of our time spent building them. At the

public library we found a book written by F.B. Evans that contained diagrams

of every part of a single-engine plane, with words supplied by Orville and

Wilbur Wright.

We learned why our planes crashed and what we could do to make winners

of our failures. We learned about pitch, roll, and yaw, and spoke in terms of

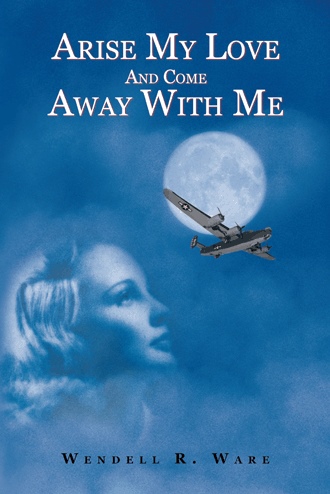

Arise My Love And Come Away With Me

dihedral and torque, and why weights and balance were so important. We

spoke in a language that we called “Airplane.”

We read stories of World War I flying aces that had replaced our heroes of

yesteryears, Tom Mix and Ken Maynard, with stories of Eddie Rickenbacker,

who destroyed 21 German planes and became America’s ace of aces.

After the war, Rickenbacker, a member of the famed 94th Hat-in-the-Ring

Squadron, became president of Eastern Airlines. Frank Luke gained ace fame

by destroying German planes and balloons. His name lives on to identify an

Air Force base in the city of his birth, Phoenix, Arizona.

When I was ten years old I started hanging around the Albert Whitted

Airport. After church one Sunday, I begged my mom and dad to take me

to the airport. It wasn’t an easy sell. I had to do a lot of begging, but with

a sniffle or two, and promises made that even an accomplished politician

couldn’t keep, I carried the day . . . I thought.

Our auto, an Oldsmobile touring car, changed directions and headed to

the Bay Front Airport. My sisters, Irene, age 14, and Ruth, age 13, had other

plans for a day that did not include the airport. I thought their arguments

were flawed, and in a loud argumentative voice let them know how much I

didn’t like silly old girls.

“One more word out of any of you, and we go home. Now, calm down

or you will stay in your rooms for the rest of the day.” When my dad spoke

like that, it was an honest-to-gosh non-negotiable edict. Mom added her

soothing voice, with logic that we all understood, and utter silence from the

back seat reigned. We drove down Second Street south to Beech Drive, and

Dad parked the car at the curb. Before me, lay the most beautiful sight in the

entire world.

Along the margin of St. Petersburg’s strip of Tampa Bay lay the airport

named for Albert Whitted, whose father was one of the pioneer developers

of our city of sand and palmettos. Albert, his son, was a U.S. Naval flight

instructor stationed at Pensacola, Florida.

One unfortunate day he was flying over an area designated for flight

training, teaching a cadet how to recover from stalls on take-offs and landings,

when a stay wire on one of the wings of his biplane snapped. The plane,

about a hundred or so feet in the air, rolled to the left and crashed into a

field at the end of the runway. Albert was killed, but the student lived to fly

again.

Along the south boundary of the field stood two hangars; one for airplanes

and another giant hangar for the Goodyear blimp Mayflower that, along with

the tourists, spent the winter here. There was an attached single-story office

building that one day would become the home office of National Airlines

Inc.

I started walking along the fence to where a small crowd had gathered

to watch, as two men were preparing to take their place in the cockpit of

the Ford tri-motor passenger plane. The passengers were probably tourists

adding one more experience to their winter holiday to take north with them.

I watched as the plane taxied to the east west runway and turned east into

the wind. I could see the pilot and co-pilot as their hands moved easily about

the cockpit adjusting dials and flipping switches. I could only imagine what

else they were doing; but I did know that their hands, eyes, and hearts knew

the magic of flight.

I watched spellbound as the three roaring engines pulled the plane faster

and faster down the runway. The wheels of the plane were, like dipping a

toe into bath water to see if it’s too hot or too cold, cautiously testing the

air for the right moment to break the bonds of earth. The plane found that

precise moment and, like an aviation expression of the day, “climbed like a

home-sick angel” into a beckoning sky.

When the plane disappeared into that bright Sunday morning sun, my

imagination took flight. I had loosened one of the ties that bound me to the

earth. I heard my father say, “Let’s go!” With visions of flight safely locked

away in my memory, I followed him to the car.