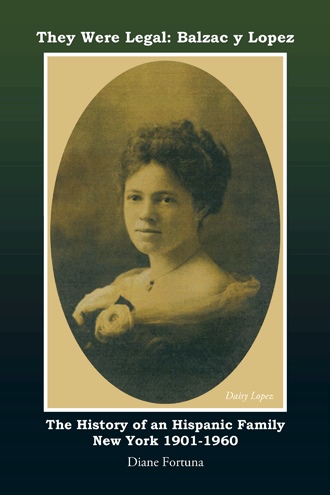

From "A Flower for Daisy":

Engraved on the stone are the words, “Daisy Lopez Fitzi. Greater love hath no man than this: that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

What could Daisy have done to merit such an inscription? Had she been heroic in some way? Had she saved others and sacrificed her own life?

The archives of the Kingston, Jamaica newspaper, The Gleaner, provide the answers to these questions. In early April 1911, the daily carried the notice of Daisy's death relying on information supplied by her brother, Christopher.

A Jamaican’s Death

Dr. Lopez, the dentist, yesterday received a letter from New York telling of the death of his sister, Miss Daisy Lopez, in the great fire. She jumped from the ninth floor and was injured. She was removed to a hospital in New York, where she died on the 27th ult. Miss Lopez was injured in the 1907 earthquake in Kingston, and left afterwards for New York, where she joined her brothers and sisters.

“Great Horror: Details of New York’s Terrible Blaze,” The Gleaner, 5 April, 1911, 14.

In a story five days later, the newspaper added her married name and the justification for the quotation on her tombstone.

A Jamaican’s Heroism

The funeral of Mrs. Daisy Fitze, one of the two young women who were found alive after jumping from the ninth story of the Asch building, in Washington place last Saturday, was held last night from the Spring Street Methodist Church.

Mrs. Fitze, who died at New York Hospital, was declared by the Rev. Roswell Bates, pastor of the church, in his funeral sermon, to have sacrificed her life in saving others. He declared that she had told him before her death that she had directed more than fifty girls to a stairway, and had jumped to the street only after she found that escape was impossible for her.

“Terrible New York Fire,” The Gleaner, 10 April, 1911, 14.12

Perhaps the knowledge that she had saved so many eased Daisy's final hours. To her sisters, Ianthe and Louise, and to her brother-in-law, Pepìn Balzac, it seemed a terrible irony that having narrowly survived the 1907 Kingston conflagration, she had delivered herself all unknowingly to the fire next time in New York City.

*****

Young woman, eyes swollen shut. Jumped from ninth floor to avoid factory fire. Brought to hospital in semi-conscious condition. Broken left iliac crest of pelvis, considerable hemorrhage, broken right humerus. Contusions and abrasions on face, head. Patient rallied from primary shock, but secondary shock followed, and condition rapidly became worse. Died sometime after 2a.m. 3/27/1911.

-- New York Hospital medical records of Daisy Lopez Fitze, victim of Triangle Waist Company Fire

City officials called for a day of mourning and announced a public funeral parade to take place twelve days after the Fire. By then, all but the unidentified dead had been buried. As part of the procession, eight flower bedecked coffins carrying their remains would be accompanied via ferry to the Evergreens Cemetery.

On April 6, the weather was terrible. Because of the driving rain, Pepìn had talked Louise into staying home with 10-month-old baby Joey at their 16th Street apartment. She had wanted to pay her last respects to her sister but had been close to emotional collapse since the burial service for Daisy on March 30.

Around 1p.m. Pepìn closed his printing shop and strode east on Sixteenth Street to Fourth Avenue to stand silently with hundreds of other onlookers, watching the procession from under big, black umbrellas. Drenched, those without umbrellas marched solemnly in the pouring rain. Many were hatless. Almost all of the mourners carried small American flags draped in black crepe. As the parade progressed, one saw a few banners reading “We Mourn Our Dead.” From uptown and downtown, thousands walked silently in memory of the victims. Tens of thousands lined the long, sodden routes converging on Waverly Place, around the corner from the Asch Building.

Public outrage against the company's owners, Max Blanck and Isaac Harris was so formidable that by mid-April they were arrested for manslaughter in the first and the second degree, charged in particular with the death of Margaret Schwartz. Both men immediately made bail.

Their trial didn’t begin until early December. During it, Max Steuer, counsel for the defendants, managed to destroy the credibility of one of the survivors, Kate Alterman, by asking her to repeat her testimony a number of times — which she did without changing key phrases that Steuer believed were perfected before trial. In his summation, Steuer argued that Alterman and probably other witnesses had memorized their statements and might even have been told what to say by the prosecutors. The defense also stressed that the prosecution had failed to prove that the owners knew the exit doors were locked at the time in question.

Soon after Christmas, 1911, the trial came to an end. Deliberating for less than two hours, the jury voted to acquit.

In the next couple of years, the owners did incur some related expenses. In August 1913, Blanck was arrested and fined $20 for locking the door in his new factory during working hours. In addition, Blanck and Harris lost a civil suit when 23 families of Triangle victims sued them for damages. In March 1911, almost three years after the fire, the plaintiffs won compensation in the amount of $75 per deceased worker. Overall, despite these minor set-backs, the owners made good money on the Triangle Waist Company Fire. Their insurance company paid about $60,000 more than the reported losses, or about $400 per casualty.

Pepìn followed the aftermath of the fire with an increasing sense of disillusionment. Justice, it seemed, had been blind-sided, and Corporate Greed, attended by a slick lawyer, had gone to market and done a jig all the way home.