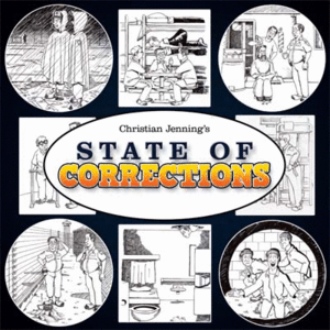

State of Corrections

by Christian Jenning

Book Cover & Preview Text

In the fall of 2004, I sat down to begin sketching the illustrations that appear on the following pages. The stool I found myself sitting on was attached to the back wall of a deliberately cold and unwelcoming cell in a security housing unit (SHU). An SHU can be likened to a sort of jail within a jail. As I sat there looking back over the span of my imprisonment, I began to recall the series of events that would eventually culminate in State of

Writing a book about my personal experiences while on the inside, as it were, had been suggested to me on more than one occasion. My family encouraged me numerous times. Friends, at one point or another, did the same. And while the encouragement was tremendously flattering, it was also a bit bewildering. I just wasn’t convinced anyone other than family and friends would find me that interesting or that I could actually write a book. Ultimately, it was a comment made by a prison guard that got me thinking maybe, just maybe, I can do this.

Despite my lack of confidence, I had been interested in writing a book long before any added encouragement from friends, family, and acquaintances. I didn’t know where or how to begin. Earlier in my prison term—the bitter years, as I think of them—I thought about writing a book and had even toyed with a number of different ideas. At one point, I settled on the idea of compiling the personal stories of other prisoners who, like me, seemed to have an incredible talent for seeking out, finding, and then retaining not-so-incredible lawyers in whom to entrust their freedom—and indeed, in some cases, their very lives. It soon became apparent after talking with literally thousands of other prisoners about their cases that I would not be writing a book on that subject after all. There were just too many horrifying tales, and it became impossible for me to separate fact from fiction.

Aside from the frustration of being unable to pin down any one idea to write about, there was also one painfully obvious hurdle everyone seemed to have overlooked: I didn’t know the first thing about writing a book. I’m not a writer. The truth is, I don’t even like to write. I answer letters, but only because it is the polite thing to do. What I am, however, is a guy with an “okay” talent for doing artwork. I’ve been able to draw for as long as I can remember, ever since I was a kid really, but it wasn’t until coming to prison that I began to pursue it seriously.

The majority of the artwork I’ve done while a prisoner has been for the correctional staff—that is, prison guards. I quickly learned it was a lot more beneficial to do work for them than my fellow prisoners, and work I did. I’ve drawn everything from portraits and tattoo patterns to football banners and business logos, but in recent years, my cartoon drawings have been the most popular among the staff.

The first dozen or so individual drawings of the SHU staff were done over the course of several weeks. The initial motivation was simple enough. By design, the SHU is an incredibly boring place to find yourself in, and, as a result, the behavior of prison guards can be very entertaining. Each sketch reflected their behavior as I observed it over the course of an eight-hour shift. No matter how seemingly inconsequential that behavior was, I managed to find a little humor in it and transferred it onto paper. In addition to the individual sketches, I also worked up a large nineteen-by-twenty-five-inch drawing of the entire morning shift, the “second watch” as it is called in prison vernacular. Using bits and pieces of tape scraped together from every available source, I stuck the drawing on the wall nearest my cell door where the guards were certain to see it whenever they happened by. Sure enough, at breakfast the following morning, when the guard serving breakfast leaned toward the narrow window to hand me my tray, his attention was quickly drawn toward the wall where, among other familiar faces, he found his own staring back at him.

Watching the expression on this guy’s face as it graduated from a cold curious stare, not quite knowing what he was looking at, to complete surprise at having recognized himself in the drawing, had a profound and lasting effect on me. Until that morning, I had never witnessed the subjects of my work at the precise moment they gazed at the finished drawing for the first time. After breakfast, every guard working the SHU that day found his way to my cell, each one curiously peering through the tiny window to see how I had depicted him. Some could not believe that I had picked up on a certain behavior they were sure was not apparent to anyone else. Others were just pleased I hadn’t drawn them in a less-than-flattering manner. That day would turn out to be the most memorable day I would spend in the SHU during that particular six-month stay.

Later that same day, and after the morning’s excitement had died down, the guard who had served my breakfast returned to ask if I took requests, and shared with me some personal insight about his partners. During the course of our brief conversation, I showed him some of the individual sketches I had done, including several where he was the subject. As he looked over each one, laughing with amusement, he asked me if I had ever thought about compiling them into a book. In that moment, the concept for this book was born.

Rather than attempt to write about the bigger, broader, and more noble issues commonly dealt with in prison, such as the injustices claimed by so many, I would be focusing instead on drawing that which I know—the lighter side of prison life. I would spend the remainder of that day and most of every day since working on this effort. I began working on the title first—which, surprisingly, turned out to be the easiest part of putting this book together. With thirty-four adult prisons dotting the

Book Details