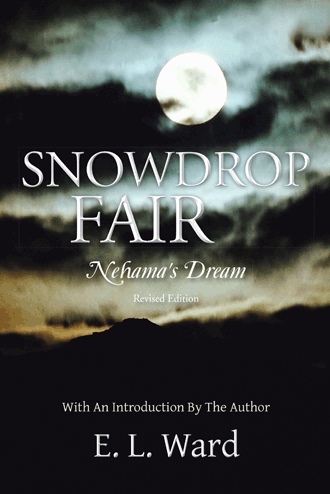

(The following is an excerpt from the Introduction) Snowdrop Fair: Nehama’s Dream is a long narrative poem that follows the pattern of a literary device known as a ‘dream vision’. When I first published this poem in 2012, I believed the narrative would stand on its own merit, and that my notes at the end of the book would be enough to explain the literary pattern I had used. But a few readers wondered why I hadn’t placed the notes in the beginning of the book, as an introduction to a largely unfamiliar genre. Their musings made sense to me; so, for this edition, I’m offering in the following paragraphs an overview of dream visions: a description of their basic features and a brief summary of the genre’s place in European and American literature, all of which is designed to give you a little knowledge that might enhance your understanding of the dramatic structure. The story itself – the dream – can be entered without your reading the remainder of this introduction. At its simplest level, a dream vision is a first-person account, in poetry or prose, of a dream that takes the following course: 1) the dreamer (usually a male) falls asleep in the midst of some life crisis, emotional or experiential; 2) he finds himself in an idyllic natural environment, often a garden filled with plants and animals; 3) he meets a guide figure who instructs and/or leads him through one or more (allegorical) visions, usually about religion or love; 4) he may question the guide figure about the importance of the visions to his life, or he may attempt his own conclusions; and 5) something within the dream causes him to awaken before the full significance of the dream can be explained. Although dreams have been the subject of art and literature throughout the ages, the pattern of a dream vision developed very early in the history of European literature, around AD 400, and continued its popularity until about the 15th century. Literary works composed according to that pattern were mostly poetic allegories, some of which used lavish alliteration; and they frequently presented sweeping views of history or of the afterlife in heaven or hell, or both. Themes ranged from courtly love to the soul’s quest for spiritual harmony with God. A few of the more famous authors and/or works during the heyday of dream visions (13th and 14th centuries) were Guillaume de Lorris and Jean de Meun (Roman de la Rose); Dante Alighieri (The Divine Comedy); Geoffrey Chaucer (Parlement of Foules and Book of the Duchess); William Langland (Piers Plowman); and Pearl, a complex, late 14th-century rhymed visionary poem by an unidentified author. Since the Middle Ages, interest in dream visions has reflected changing cultural trends. (This ends the sample of the Introduction.) (The following is an excerpt from the Prologue) Listen. As life is brief, and I Was long in learning, age counsels me, Pushes against me to apply My words faithfully; so I must free Myself from the hard tyranny Of fresh, poetic lines to tell You a dream that was both dreadful And lovely. It happened in the why And where of a long, blustery night When sleep fields of Ezekiel sight Opened and I felt a holy sigh And whir of Spirit stirring light. It was a curious, cold day That night. Flocks of dark-eyed juncos Huddled within dense brush to doze At the edges of woods. Iron-grey Branches of weakened trees broke, flew Against other trees with loose bark, Scattering debris. The winds blew No warmth, nor song, nor did they mark That owls earnestly scanned the ground From fence posts, slowly turning their heads In search of voles scuttling around Clutter in grass and garden beds. (This ends the sample of the Prologue.)