For my next mission, I would be flying with Bubba Houser, another Ft. Rucker IP. We would be flying trail for this mission. That morning, as we got ready to go, I had asked Bubba if he would fly in the right seat because I was more used to the left seat and liked it better. I also thought that he might like flying in the right for a change. Bubba, being an easy going guy, quickly agreed. Bubba and I had been following Doffis and Jeff, my roommate, around Baghdad all day, and were heading northeast out of Baghdad, when suddenly a bullet came through Bubba’s chin bubble and traveled under his seat. It finally hit something solid and made a sharp bang. We could all feel it in our feet. We scanned the buildings in front of us, looking for the sniper that shot us, but we couldn’t find him. This guy would get away. As badly as we wanted to kill him, we couldn’t spot him.

Bubba was flying when this particular bullet hit us and asked me to take the controls while he checked things out. After looking at the bullet hole, he simply looked at me and said, “See if I ever trade seats with you again, asshole.”

Once again, I had to call for maintenance to check for battle damage as I landed; this time, at least, it was back at Balad. When we shut down the aircraft, there were several people there to assess the damage and determine what to do with the aircraft. For only getting hit with one round this time, it did a surprising amount of damage under Bubba’s seat. It actually sheared the head off a bolt that held two control rods together.

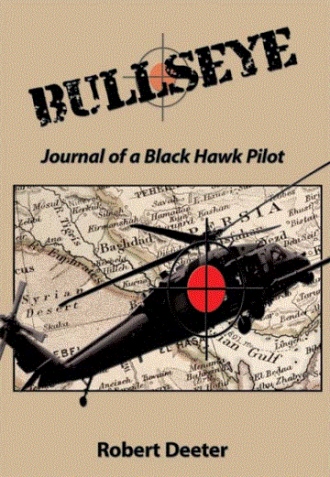

As people milled about, I noticed my roommate, Jeff Alston, was looking under the aircraft at the belly of my bird. When I asked him what he was looking for, he said loud enough so that everybody could hear, “I’m looking for the damn bull’s-eye,” followed by “Whadaya have, a bull’s-eye painted on your helicopter, Deeter?” And then, the next words out of his mouth were “We’re gonna have to start callin’ you ‘Bull’s-eye Bob.’” When he spoke those words, all conversation stopped, and everybody looked at me. It was like that old E. F. Hutton commercial, where silence falls over the room. I could see it in their eyes. I knew instantly that this would stick to me like glue, and for the rest of our deployment, I would never shake it.

Within hours, everybody was calling me Bull’s-eye. That very evening, someone at the chow hall overheard me and a friend talking about the latest bullet hole and asked me if I was the guy they were all calling Bull’s-eye. Within a couple of days, even the battalion commander was calling me Bull’s-eye. It was a nickname I would never be able to shed.

At first, I didn’t care for the nickname. It was on the daily mission board, along with anything with my name on it, and it seemed people couldn’t wait to say it when they saw me. A week or so of this went by, and late one night, as I was climbing into bed, I said over the wall lockers that separated us, “Jeff, you’re an ass.”

His reply came back over the lockers, in a humorous tone: “Why, Robert, whatever do you mean?”

I said, “You know what I’m talking about, butt head. You had to blurt out ‘Bull’s-eye Bob’ on the flight line in front of everybody, and now I will never get rid of it.”

There was a long pause.

“Gee, Bob, you should be proud. It’ll be something to tell your grandchildren about. You actually have a nom de guerre of sorts.”

“Nom de guerre? Right, Jeff. There’s Stormin’ Norman Schwartzkopf, Old blood-and-guts Patton, Black Jack Pershing, and Bull’s-eye Bob. Somehow, it’s not quite the same.”

There was another long silence.

Then I heard him laughing, sort of snorting the way someone does when he or she is trying not to be heard laughing. I guess I began to see the humor in it. I couldn’t help but laugh. We both had a long hard laugh.

A couple of things stayed with me from these first couple of weeks of combat flying. The first was that it’s better to constantly vary your altitude and heading by small increments than to wait for the bullets to start flying and have to make large control inputs. Because if you suddenly start making big jinks and jags, you have to think about your proximity to structures and other aircraft before you start. And if you’ve been flying along straight and level for a while, their first burst of fire might find its mark.

The second realization came to me as I chided Bubba about how he close he was to getting "the boys" shot off. It occurred to me that every time I flew in Iraq, I would always be only one lucky shot away from going home in a bag. The same bags we so often picked up at outlying CSHs (combat surgical hospitals) and delivered to BIAP for further processing. We called these hero missions.