My mother was riding -- by herself -- in the London Underground. A stranger in England, her thoughts were not of her home and husband in Germany. Instead, she was thinking of Paris where, last summer, in the Ritz Hotel, her baby had been conceived. She wondered if it would be a boy or a girl.

Lotte Rosalie Friedmann’s reverie was interrupted when she felt a twinge, a sudden pain, and got off the subway train, although it was not her stop. She moved gingerly because she carried heavy shopping bags and was very pregnant.

The baby was not due yet, it was too early. Was that a contraction? No, it couldn’t be. She had almost convinced herself when she felt it again. It must be a contraction!

What should she do? So far from her husband and her German homeland, not near her temporary home in London with his brother and his wife.

It was mid-March, 1934, that my father thought of sending his wife to London so the baby would have dual citizenship, British and German. It might come in handy now that Hitler had come to power.

Now Lotte Friedmann slowly followed the crowd to the exit. The station was considerably below the surface and a long, torturous stairway faced her. She proceeded slowly upward and onward, climbing one steep step at a time, keeping to the right as faster folks hurried past her.

Lotte trudged up slowly; the stairs seemed an almost insurmountable obstacle, extending ever higher, practically getting steeper as she climbed ever upward. Her pregnancy bulge was in her way. Suddenly, the baby kicked, causing her to become short of breath as she climbed slowly upward.

Taking her time, letting others pass her, Lotte Friedmann made her way up toward the surface. It was exhausting. Her heavy shopping bags were a real burden. She felt the contractions, but even more, she felt lonely -- indeed, she really was all alone now.

Just then her water broke! The baby was coming! It was much too early! It wasn’t due yet! Her husband wasn’t here! And now she was wet! Cold and wet and alone and tired of climbing. She stood still a while, catching her breath.

Then she continued onward and upward, forcing herself to climb the steep stairwell; exhausted, embarrassed, frightened, a stranger in a strange land. She felt angry at her husband for sending her away -- all alone now -- to this foreign place in her condition.

Nevertheless she kept slowly mounting the long staircase, carefully, painstakingly.

Finally, she reached daylight at street level. It was a bitter cold day in London in March, 1934. Wind whistled down the strange streets. There is nothing as lonely as a dreary day in chilly, wintry, foggy London town.

She had arrived in the Stepney sector of Cheapside in East London. One of the worst sections. It was where Jack the Ripper had terrorized London. He had murdered women who were alone! And she was truly alone. Now she was terribly frightened. She knew he had never been captured and was fearfully aware of how lonely and homesick she was.

London’s worst slum, one of its oldest areas, this was the rundown district where the poor and homeless, the sleazy and the criminal, still lined the cold sidewalks. It was London’s highest crime area. There were many other criminals still out there now. They still preyed on women who were alone. Lotte Friedmann shivered in the cold March air.

Luckily, there was a taxi there to take her to a hospital. The driver said Jewish Memorial Hospital was not far. “Jewish” sounded good … but the area didn’t look good.

People from that area are called cockneys and have a distinct accent, different but not distinguished. It was Eliza Doolittle’s awful cockney accent that Henry Higgins corrected. Cockneys also speak with a unique rhyming slang. They substitute rhymed phrases for certain words, saying “trouble and strife” instead of wife, “box of toys” for noise, and “dickory-dock” for clock.

The traditional definition of a cockney is anyone born within the sound of Bow Bells. And I was born in the closest hospital to London’s famed Church of St. Mary-le-Bow, whose steeple houses the tall campanile which contains Bow Bells. They rang that day. They still ring every day.

I was born there on March 28, 1934. But I don’t have an English or cockney accent because I left England when I was 28 days old. My parents took me home to Germany. My father got to London before my mother and I were discharged from the hospital.

Everyone agreed that I had my mother’s hairline, forehead and eyes. And people said I looked like my father from the nose on down. All the way down!

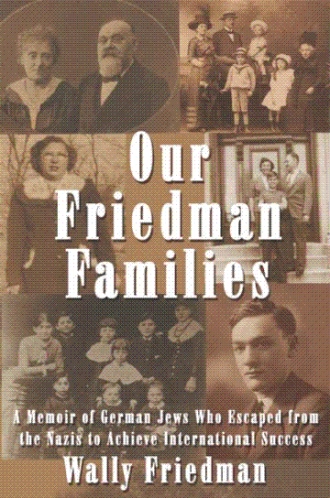

Both sides of the family thought I was indeed a real Friedman, with a double ‘n’ at that time. A real Friedmann, they agreed, because not only was Friedmann my father’s surname and now mine, but my mother’s maiden name as well! (They were not related until they got married; there are lots of Friedmans in this world, most of whom are not related to us.)

They had a hard time coming up with a name for me that was both German and English as well as one that, in Jewish custom, is a reference to a deceased ancestor. One idea was to name me after one of my father’s two little brothers who had died in infancy. They were Walter and Ludwig. My parents both preferred Walter, and so do I. It was a German name, as in Walter von der Vogelweide. But was it English?

“Oh, yes, definitely,” my father’s brother Paul’s son Herbert said. “Think of Sir Walter Raleigh -- that’s as English as you can get!” So I was named after him.

With a double dose of Friedman, I’m a real Friedman, all Friedman and nothing but Friedman. And I am an only child. Therefore, while we are almost all Friedmans in this memoir of my many Friedman families, I am the most Friedman of Friedmans!