The waves rose and fell against the shore in a steady, deliberate rhythm, as though nature itself had rehearsed the moment. A light breeze drifted through the warm mid-June air, and the sun stood high and unchallenged in the sky. The entire coastline appeared calm—so calm any newcomer would never have imagined how violent the weather could turn. The tranquility was deceptive, creating the illusion that the sea was always this gentle, this obedient.

It was the kind of atmosphere the organisers always wished for, although it made little difference to them whether it was different and more disturbing. The chief organiser for the event was a man nicknamed Commander Apollo. He was a French native speaker, age forty-five. Commander Apollo had been dismissed from the French Navy after he was court-martialled and convicted of an offence for smuggling alcohol on board a ship without declaring the items. He had never forgiven his country and the French authorities for his sack and always said it would be his time for revenge, however long it took.

Commander Apollo arrived at the beach in Calais at midday, ahead of his contingent of men and women who assisted him in the task of seeing to the ferrying of asylum seekers from Calais, France, to Dover, England. He had been in the business for five years. Whenever it came to his turn to supervise the ferrying of people from Calais, he did his job with military precision, ensuring no stone was left unturned, rebuking anyone under his control and command who failed to carry out his instructions, sacking anyone on the spot he felt was not good enough to remain in his team, and threatening some of his staff with torture. Commander Apollo was known for his brutality in his dealings, not only with his henchmen and foot soldiers but also with asylum seekers and refugees seeking their transportation from Calais to Dover.

As he stood on the beach at Calais, he surveyed the whole area, looking to his left and to his right and straight ahead of him into the sea, as far as the eye could see. He smiled. He nodded his head several times, punching the air several times, saying to himself, it was another good day for him, another easy assignment, and it was going to be as simple as eating breakfast.

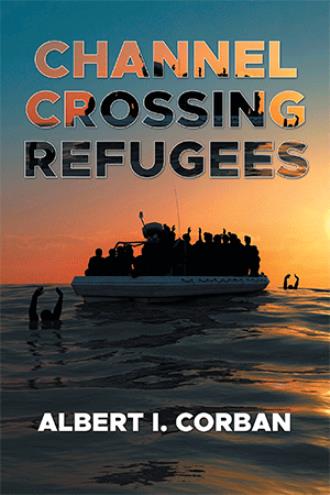

Thirty minutes later, at about one o’clock, buses carrying refugees started to arrive, hundreds of them. The organisers had arranged for one thousand asylum seekers to be ferried across the English Channel.

When the refugees arrived, including the children, the organisers moved with purpose. They formed ten groups of one hundred, split each into two units of fifty, creating twenty controlled subgroups. Each unit was assigned a dinghy fitted with ten ten-horsepower engines for the crossing. Some boats had made the journey before; others were facing the Channel for the first time.

The vessels were built by hobbyists who learned from one another, men with no formal training but enough skill to assemble something that could float. Their dinghies cost far less than those produced by licensed manufacturers, and it suited the organisers. Cutting costs was the core of their operation. Profit came first, and they never hid it.

Twenty assistant commanders oversaw the operation, each supported by a team of three. Their job was simple: push the refugees into the dinghies and keep the process moving until launch. They shared Commander Apollo’s ruthlessness, not by nature, but by instruction. Once a dinghy reached the shore, it had to be used. Its condition didn’t matter. No one’s doubts or fears changed the order.

After the refugees were subdivided into groups of fifty people, the dinghies arrived in two lorries. They were taken to a designated location on the beach, where each could be inflated. When inflation was taking place, and those doing the job observed a problem, such as air leaking out of a dinghy, however small the hole, they had to report it to Commander Apollo. After about fifteen dinghies were inflated without any problems, the operators found that the sixteenth was letting air out and forming bubbles when inflated in a pool of water, as was the usual practice during inflation. The head of the inflation team, Francis Alfred, a fifty-five-year-old retired fisherman, picked up his mobile telephone and dialled Commander Apollo to notify him.

“Sir, we can’t use this one! There is air coming out, and it is not going to be safe, sir,” Alfred said slowly, looking at the dinghy in front of him while his workers waited for his order.

“What? I don’t give a shit what you are saying about the dinghy. We have to use it! If we don’t use it, how will the people get to Dover? We are going to use it, and I believe it will be safe!” Apollo screamed as he got up from where he was sitting, waiting for all the dinghies to be inflated.

“Sir, I hear what you say. I am concerned the dinghy is going to get into trouble when it gets into the water. It’s not safe, sir.”

“Nonsense! I don’t give a damn about safety! Now inflate the dinghy and use something to seal the leak. Do not tell the pilot about it. Do you understand me, Alfred? If any word goes out about it, I will hold you responsible, and you will pay for it, and it is not going to be funny! Now get on with the job!”

Apollo cut off the phone, preventing Alfred from replying.

As Apollo sat again, Alfred’s warning pressed into his thoughts. A knot formed in his chest as he remembered a lesson from naval school: the smallest cut below a waterline, no wider than a needle, could spread under the force of the sea. Pressure would turn a flaw into a wound, and a wound into a breach. Sooner or later, the largest vessel could be lost.

Apollo brushed aside his concern as he stood up and swore, remembering again the events leading to his dismissal from the French Navy.

Moments later, all twenty dinghies were ready to be used, the sixteenth dinghy having been sealed with heavy-duty cello tape. The team had resealed the place again and again, hoping it would be enough to keep the dinghy safe. With reluctance, not that he had any choice, Alfred let the sixteenth dinghy go along with the others.

Once the dinghies were placed in the sea, near the shore, in front of each group of refugees, the pilots, after receiving the signal, emerged from a bus where they had been waiting for instructions. The pilots, most of them fishermen, many with no experience piloting a dinghy across the channel, but only receiving instructions on how to do the job a day or two before, scrambled to decide which dinghy to pilot.

The pilots were grateful to have been selected for the job, each receiving £10,000, which represented a year’s salary from their regular jobs. The selection of pilots was conducted by the organisers in a secretive, underground, and confidential process, with the background of each pilot being thoroughly checked.

Once the pilots were at the head of each dinghy, the refugees were lined up and began to mount the dinghies. It was well choreographed, with embarkation almost simultaneous. Each dinghy was constructed to accommodate thirty people. Still, the organisers felt confident it should be able to take fifty people, as they had done in the past, again with the aim of maximising profit.

The refugees felt a deep sense of elation and excitement as they boarded the dinghies, at last beginning their dream of reaching Dover, England. The atmosphere continued to remain calm, the gentle breeze lashing on the shore and on the refugees and everyone around, as if they were being caressed by nature.

The refugees were from different countries in Africa, Asia, South America, and Europe, and one would have thought it was a United Nations of Asylum Seekers, with every part of the world represented. In dinghy 16, amongst the fifty refugees, were two families, two women, one