As I fished from a sun-drenched sandbank, Gramps stood thirty feet upstream in knee-deep water, littered with blotches of shade. A slow-moving current pressed against his worn rubber hip boots and tested the seal of several homemade patches. He craftily positioned himself to drift his worm under some well-shaded logs and remain undetected by the fish. The olive-gray water gently boiled as it encountered the logs, casting a mesmerizing spell.

While he stood there in nature’s gentle hand, it struck me that he literally became part of the river, as if he sprouted up and grew naturally like the vegetation around him. The river seemed to accept him as one of its own aged children. It was then that I hoped to grow up with this stream in the same manner that Gramps grew old with it.

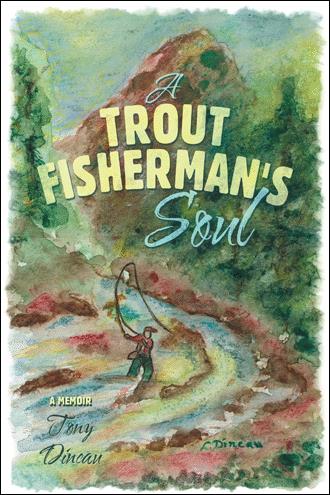

I intently watched my sixty-four-year-old grandfather and studied his every move. His long-sleeved button-up shirt and dark slacks covered a slight frame, while an off-white fishing vest with bulging pockets hung casually over his torso. Hanging loyally by his left side was a wicker creel that occasionally flinched from a flopping trout. Around his waist, a brown leather belt fastened his green cylindrical worm can firmly to his front left hip. His balding head held a faded yellow ball cap that had a sewn-on patch in the front depicting a trout fisherman. His gold metal-rimmed bifocals were perched firmly on his nose, holding steady throughout all his movements. In his right hand he held his limber, seven-foot long black pole with grace, while his opposite hand gingerly stroked fishing line from the blue and gold Perrine automatic reel. On line’s end were two split shot sinkers that sat above a piece of night crawler on a No. 8 single-barbed hook. The concentration on his tanned, whiskered faced was evident, much like an eagle eyeing his prey, yet there was still an easy way about him. He was a man in his element.

Gramps’ motions were smooth and nimble. His first underhanded cast was effortless, almost timeless, as he pitched his line out like a fine silk thread. The arcing worm settled so lightly on the water’s surface that it appeared to dissolve out of sight, seemingly beating the effects of gravity.

His first drift under a log sent his pole into convulsions as a thick, thirteen-inch brown trout slammed his bait. Gramps set the hook with a panther-quick wrist snap and deftly fought the fish to open water, keeping his rod tip up and his line taut. This technique helped keep the hook firmly planted in the trout’s mouth. After a fiery tussle, the fish tired and Gramps gave him the “ole heave ho” to the brushy bank. Since he didn’t carry a net, he typically banked the bigger fish. This, of course, sometimes led to nasty line entanglements, but it was worth it. Losing a nice trout was painful and frowned upon by Gramps.

Gramps laid the thirteen-incher in his new wicker home and went back for more. Not out of greed, but more out of duty. A few drifts later his pole tap-danced again as a scrappy twelve-inch brown fell victim to the master. Subsequent drifts led to several more smaller browns and rainbows that he released without leaving the stream. What a pro! He mastered the fine art of catching trout thanks to a combination of skill, experience, and a good dose of patience.

While Gramps worked his magic, my action slowed after I had caught a few.

“Pssst, Tony, sneak over here and try your luck,” Gramps called and waved.

I stepped across the sandbank, skirted the brush edge, and slipped back into the stream beside him.

He pointed to where he’d fished and whispered, “Now it’s your turn to read the stream.”

I jokingly replied, “So, when does the next newspaper come floating by?”

It isn’t that easy. Reading changes in water depth, current, and cover is an art that can’t be mastered with books. Experience is the best teacher. Now successful veteran anglers, they learned to think like trout, like where they might hide and when they might strike. A trout’s world is fairly simple—stay hidden, conserve energy, eat with care, and stay alive long enough to reproduce. An angler’s savvy takes center stage when drifting a worm into a trout hole, not only by reading the water, but by feeling the line as it bumps off bottom and bangs into hidden cover. Since we can’t see into most holes, with some being six feet deep or so, our sense of feel becomes our eyes under water, and that sense also triggers when to set the hook.

To watch a seasoned fisherman on his favorite stream, to watch Gramps at the Flag, was poetry in motion.

Inspired by Gramps’ guidance, I flipped my worm into a shaded eddy that Gramps hadn’t fished. The trout were getting the best of me when suddenly my pole bent sharply. Out of instinct, my wrists snapped upward for a clean hook set. The trout responded with rhythmic downward pulls that eventually eased as the fish tired. Moments later I gave a flipping, ten-inch brown a heave-ho to the nearest bank and then pounced on it immediately.

Gramps yelled to me, “Hey-hey Tony, Feesh-On-Ralphie!” That excited stream call was our family patent that we used whenever we hooked a defining fish. The term Feesh, of course stood for fish, but in true “Ralphie” style, Gramps added a little flair to his stream lingo.

While I quivered from my catch, Gramps moved closer and slapped a tanned hand on my shoulder and exclaimed, “That’s my boy, that’s my boy!”

Later on, as we cleaned our fish on the river, Gramps gave me a silver pocketknife. That small knife came from the Wabegon Bar and Grill where Gramps worked and it represented a merit badge on the stream. Now that’s how to hook a kid on fishing!