HER BARE FEET left wet footprints in the sand at the water’s edge. The trail of prints led from the gray sea-washed wooden steps descending from the edge of her property to the beach to this spot just short of the first outcropping of rocks along the coast line. Turning around to face where she had been and squinting into the sun, her hand raised in salute as a visor above her brows above the blue tinted lenses of her glasses, she saw that the water had already washed away most of the footprints. For a moment she felt as she imagined Gretel must have felt on discovering that the birds had eaten her trail of crumbs and she had no markers to guide her back out of the forest.

The house she had left behind, locked and shuttered against the sea and the salt and the sand carried by the fresh intruding breeze, perched solid on the rocks beyond the wide expanse of beach, behind a waving man and bounding dog. Safety, said the house, and solidity and solitude, abundant solitude, and the sound of the surf and the dog’s bark and a screeching bird in flight spoke too, but the woman standing barefoot on the beach and shielding her eyes from the sun’s glare didn’t answer because no answer was demanded of her.

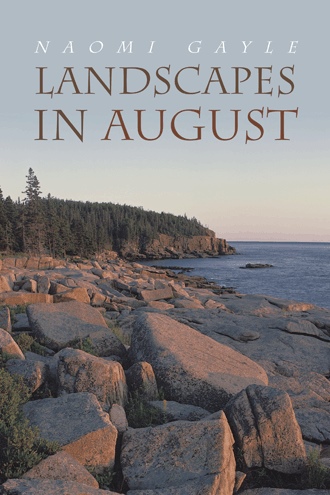

To her left the ocean pounded against itself and the jutting rocks; to her right, beyond the stretch of sand, rose low cliffs of red stone, and further down the beach, in the pathway to the sun, the man and the dog frolicked. Man and dog and she had shared this beach for five years now in morning and evening ritual to salute the rising and the setting sun. Man and dog and she and an endless succession of days that went on not caring whether man nor dog nor she existed. The man, raised an arm and moved his hand from side to side, and she did the same, and they signaled in semaphore that once again the day had begun. The dog, a setter the rust color of the rocks, bounded to her and then back again to the man and the sun and the routine of days that began and ended just this way.

The rocks spanning the shore tempted her to explore. She climbed carefully, feeling sharp edges beneath the callused soles of her feet. Five years of calluses, five years since she had worn high heels and stockings, five years of solitude and fresh air and a man and a dog and the sun rising somewhere in the east.

Nestled in a hollow just beyond the top of the rocks was an amorphous lump of soft gray fabric, gray as the sea-washed sun-drenched steps she had descended from her house to begin the journey to this moment. Where she stood, silhouetted against the sky, she could see, and be seen by, walkers on either side of the rocks, but the lump was huddled down into a niche between two piles of rocks and could be seen only by her.

She approached it cautiously, hoping and not hoping for the thrill of discovering a dead body on the beach. It seemed to breathe, a gray lump that rose and fell with the constant rhythm of a child asleep. The gray separated itself into other colors, other parts, a soiled tan jacket, the kind she had considered ordering from a mail order catalogue, faded blue jeans, black scuffed wing-tip shoes. Those shoes, so incongruous on the beach, so wrong for every other part of the lump she had now identified as a sleeping boy, those shoes belonged to the world she had left behind, the world of high heels and stockings and people she could no longer remember.

Gently she prodded the sleeve of the jacket and the creature inside stirred like a hermit crab disturbed from its shell house. A face appeared, barely old enough, she thought, to warrant a stubble, although a grimy hand emerged from another part of the bundle to stroke the chin and check for stray whiskers. The mouth moved in circles and squares, a jaw testing itself in motion, and then with a rasp as if the gears that produce sound had not quite meshed, the boy said, “What do you want?” in a manner that suggested he had a perfect right to be there, and she had no business disturbing his slumber.

“Who are you?” she asked, having no other answer ready and feeling at a disadvantage with this intruder on what she claimed as her property, although her ownership of those rocks extended no further than her imagination and the proprietorship that comes from having sat and sketched in that spot for five years now.

The eyes that appeared when the face stopped grimacing were an iridescent blue that sparkled like sapphires in sunlight. Those eyes studied her while their owner seemed to contemplate whether or not to answer her question.

“Who are you?” the voice that now matched the eyes in clarity and coldness asked.

“I live here,” she said, trying to be stern, trying to convey that it was she, not he, who was in charge. The pounding of her heart made her aware she was afraid.

“Here? In this very spot?” he asked, teasing her. “Then you had no place to stay last night. I am sorry. There was no sign or anything, so I assumed the place was vacant.”

She smiled in spite of herself. “That’s not what I meant.”

“No?” He sat up showing her how well the parts of him fitted together, then stood and stretched against the horizon, and she discovered she came just to his shoulders.

“‘For thou art long and lank and brown as is the ribbed sea sand’,” she said, forgetting she was not alone.

But he said only, “Coleridge,” and reached his arms out as if he would embrace the world.

She realized he must be older than she had thought when she had first seen his still sleepy face, the features barely sketched in, a face waiting for the imprint of experience so that others might see the history of his life etched into lines and eventually wrinkles. Yet the sadness he carried with him did not suit him, the way his shoes did not match his clothes. Standing, he reminded her of a Giacometti sculpture, a man with his feet glued to his shadow and no place to go except to fall forward into that shadow and dissolve into a formless blur.

She turned to peer back over the rocks to see if anyone was watching them, aware that she wanted to experience this moment of meeting unobserved. No man, no russet canine, occupied the bare stretch of sand between herself and her house and beyond, only streaks of paw prints and foot prints and the slowly shifting sands.

The boy stretched again and smiled and held out his hand, bending low before her in what, in another place and time, might have been considered a bow. “How do you do. I’m Rolls.”

She took his hand with mock solemnity. “I’m Susan.”

His grasp was firm and direct and like his eyes.

“Susan what?” His eyes never left her face, his hand stayed clasped to hers.

“Susan Miner. And Rolls . . . Royce?”

“Yes.” The smile crinkled the skin under his eyes, and she saw that he might have been crying.

“Really?”

“It’s a nickname. My real name’s Peter, but they call me Rolls because my last name’s Royce. I sort of like it.”

She could feel his enjoyment in the warmth of his hand still pressed firmly to her own.

Slowly he separated their hands, one finger at a time, then the palms. “Is there some place I can get breakfast around here?”

She wasn’t sure whether she had been set up, a suspicious feeling in the pit of her stomach sent a warning signal to her brain. Beware. Watch out. He could be a thief. He could be dangerous. Her system short-circuited, her brain refused to respond to the messages.

“You can have breakfast at my place,” she said.

He looked almost embarrassed. “Oh, no. I couldn’t. I didn’t mean . . . I can pay.” He pulled out a wad of bills that, even if they had been ones, would have been sufficient for many meals.

She put out her hand to refuse, then turned towards the empty strip of beach and the house beyond. “Follow me,” she said, walking boldly across the rocks, forgetting her bare feet, and then, “Ouch,” as her foot slipped between two rocks. For a moment she saw a flash of white and pictured herself plunging head first down the rocks, landing flat out on the wet sand, a trickle o