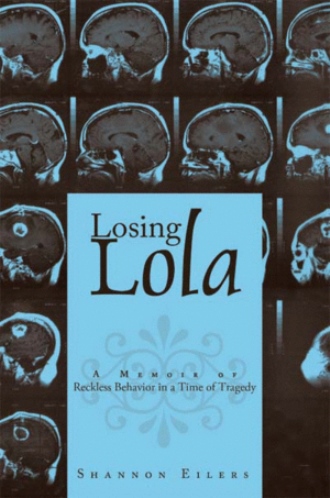

Have you ever known anyone who is such a hypochondriac that every time they get a headache they think it's a brain tumor? I'm that way. But I have a fairly good reason for my fears. My mother and her mother both had fatal brain cancer. My mom was fifty-nine years old and going to die. When her mother was diagnosed with brain cancer she was an octogenarian. What can you do to save someone with brain cancer? My mother and her mother had completely opposite ways of fighting their cancers. My grandmother fought; had surgery to remove the tumor and went through radiation treatments. This proactive plan helped extend her life by three years, but she lived those last years partially paralyzed and mute in a nursing home. Grandmother sat in a wheelchair all day. The steroids gave her a round swollen face almost unrecognizable. It was an unpleasant three years. On the other side of the spectrum, Lola did not fight her brain cancer. She did not want to live and die like her own mother.

Lola visited my grandmother every day in the nursing home. I visited often. I will not soon forget the visit when we pushed my grandmother's wheelchair to the sun room. As we ventured to the room at the end of the hallway, I held my breath to shield myself from the stench as we walked by rooms with open doors and patients with open mouths. The sun room was deserted, quiet, and stale. The windows that were there were so covered in cobwebs and dust you couldn't see clearly through them. It seemed too gloomy to be called the sun room. But it provided a much needed change of scenery. Mother and I sat on wicker chairs with lumpy, faded cushions. As we sat and thought of things to say to my grandmother, my eyes wandered across the room to a set of training bars that are used to help people walk. I was pretty sure that my grandmother would never walk again. And then I noticed that right there on the floor of the sun room, in between the bars was a human turd. No one else seemed to notice it was there and no one was in a hurry to clean it up. I was too spoiled to do anything but turn up my nose. Nice. And now that piece of human excrement is a part of my grandmother's nursing home memories.

There were days that were okay, and then there were the other days. Some days my grandmother just sat and cried, unable to tell us what she was weeping about. Some days she recognized us and some days she didn't. She often sat with her eyes closed against the horrible truth. I never did see her happy after she was diagnosed with brain cancer. And the nursing home that place had a smell you wouldn't believe. Death, illness, urine, shit, and bad cafeteria food. all in one sickly smell. Some days you could smell it before you even opened the door. Men and women being cared for there were often yelling and crying out. These sounds haunted the halls day and night. Many times they were crying out for a lost loved one they had forgotten was long gone. A few desperate patients would even try to run out the front door rushing into the fresh air and freedom. Eventually they put a lock and buzzer on the doors. My mother's tumor was inoperable. She did not fight the cancer. After seeing her mother suffer for so long, she decided she would rather spend her last months at home surrounded by friends.

I guess the decision my mother made to not seek treatment will haunt me often. I wanted this to be Mom's decision. What if she had decided to go through the chemotherapy and radiation treatments? What if the M.D. Anderson Cancer Treatment Center in Houston had some new cutting edge technology? Friends and family said the right choices were made. But we had so many options and so many decisions to work through and so many professional opinions to weigh. Can anyone make the right or wrong choice about death or how or when it will come?

The oncologist told us that radiation could lengthen her life for six months to a year. He did not talk about her quality of life. His only goal was to shrink the tumor. His treatment plan included radiation to two-thirds of Lola's left brain even though the tumor was a mere three centimeters. He also told us that radiation would not destroy the tumor nor would he be able to stop the reproduction of cancer. This tumor was going to take my mother's life. I was not ready for that. The oncologist suggested radiation every day for six weeks with an hour to the hospital and an hour back home, and chemo once a week for six weeks.

I would not say I am a strong, independent woman, but a lost child swimming in confusion. I was certainly not ready to face the challenges that lay ahead. I had never regretted being an only child. That is until my mother died. For the first time in my life I wished for a sibling. Someone who would feel the way I did. Someone to help with the decisions. Someone to talk to; someone to grieve with. God, I did not want to do this alone. I wonder if anyone left behind ever feels truly comfortable with the decisions that must be made in caring for their dying loved one.

Dilantin. Lydacane. Metoprolol. Xanax. Dexamethasone. Sennekot. Trazodone. Valium. Alprazolam. Ambien. Vicoprofen. Diazepam. Bupap. Teaquin. Duragesic. Morphine.

These are the medications my mother took during the sixteen weeks it took for Lola to die. And this is our story kept in a daily diary from her first symptom to her dying day and beyond to healing.