When I was fourteen and a freshman in high school, I took typing. I was so excited about my new skill that I asked my father if I could type his weekly reports from his out-of-town sales trips. My father resisted. He was used to writing them out in his barely legible handwriting, but I convinced him that they would look more professional typed.

My father sold a product called "Time Mist," a small machine which dispensed a spurt of aerosol fragrance at regular intervals. I remember vividly the nervous excitement I felt on the wintry Saturday morning when I sat down at the rickety Royal typewriter in my father's office at our home. As he dictated details of the people he had met and the places he had traveled to, I typed steadily without making one typographical error. But and hour later, when I proudly handed him the three-page report, I saw him scowl. Over and over I had spelled the name of his product "Time Missed."

My father was an impatient man. He could not hide the frustration he felt at having a report that was now totally unusable. I was mortified. Instead of impressing him with my skill and sharing the work he did all week, I had wasted his time. He had sold that product for years. How was it possible, he demanded to know, that I didn't know the name of the product that put a roof over my head and clothes on my back? Swallowing my shame, I pointed out defensively that he had never told me how to spell it. I suggested that his boss, who had met me, would overlook my error, which I would then correct in next week's report. My father replied angrily that there was no point in doing something if you couldn't do it right. My bitter disappointment had turned to adolescent rage by that point and I assured him that there was no way I was going to retype the report. I went storming out of his office. I never again offered to type his reports, and he never asked.

When I described this incident to my psychoanalyst twenty-two years later, he suggested that on a subconscious level I was trying to send my father a message. I wanted desperately for my father to realize that time was passing us by quickly. If we didn't find the time soon to start communicating with each other, it would be too late.

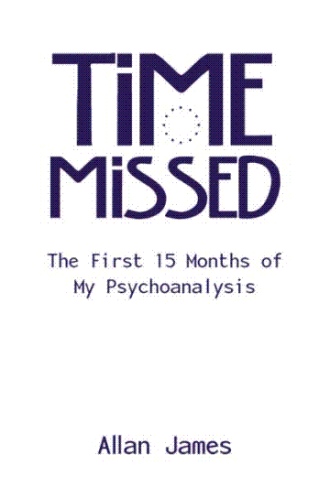

In the six years of my psychoanalysis, this was one of the few times that I disagreed with my analyst's interpretation. His explanation would sound good in a book or movie script, I told him, but sometimes, to paraphrase Freud, a typo is just a typo. Yet ever since I started writing this book about my psychoanalysis, with an emphasis on my relationship with my analyst, I have wanted to call it Time Missed. I chose that title because I have come to realize that it was not what was done to me as a child, but rather the emotional opportunities I missed with the people who were important to me, which eventually led me into psychoanalysis.