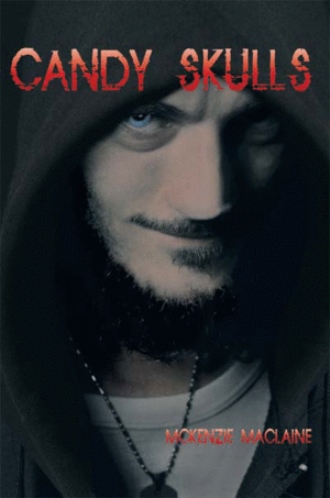

Candy Skulls

by McKenzie Maclaine

Book Cover & Preview Text

The final thuds of my worn out sandals on the sidewalk met my ears before I slowed down to a walk. Now that I was only a few feet from my objective I suddenly felt apprehensive. What if things didn’t turn out the way I wanted them to be? What if there was nothing around the corner that I put so much stake in? Where would I go from there? These questions, and the feelings associated with them were exasperating. Was this what being a human was like? All this worry and uncertainty? No wonder so many people killed themselves.

I took a deep breath, convinced myself that I couldn’t turn back at this point since I had nowhere else to go, and took the final steps around the corner. Even in the daylight the alley was somehow dark. Stepping into it was an immediate relief to my skin, now cooling down without the sunlight accosting it. The small amount of light that managed to get through cast eerie shadows on the walls, intangible ghosts threatening passersby to stay away. I squinted my eyes to adjust to the change in illumination. For the briefest of moments I was relieved when I saw there were recognizable faces here still, but it was soon replaced with dread and understanding.

Matthew Smith was still here. Anya Smith was still here. JD was still here. Michael was not. I took a step into the narrow alleyway, my eyes on the picture laid out before me. Matthew Smith, bloody and bashed, still laid on the ground. His daughter had somehow crawled under one of his arms, huddled against his lifeless form. JD was still sprawled out in an awkward position, the supernatural black mark bearing heavy on his rotting skin. The grave feeling that accompanied death lingered in the area like a fog.

The child didn’t seem to notice me yet, far too consumed by the torment of her own inner demons. Her obliviousness didn’t last long, for as I took another step forward, I accidentally kicked an empty aluminum can.

Anya gasped and looked up, sliding back into the form of her father as if he would somehow protect her. She watched me for a moment, and I made no more moves toward her. I didn’t want to startle her any further, and I certainly didn’t want to put her through any more trauma than she’d already experienced. She remained fearful, but her face softened some when she got a better look at me. I could see it in her expression; despite my new body, she somehow knew who I was. “You’re different now,” she whispered softly, still clinging to her father’s arm.

I watched the fear in her eyes fade into something less, but her trepidation was not fully banished. At first I wondered how she knew who I was, but then I reminded myself that children like Anya didn’t look at peoples’ faces. She looked at peoples’ souls. I nodded. “Very different, I’m afraid.”

Anya sat up, wiped her nose with the sleeve of her once fancy outfit. The outfit she’d picked out special to wear to Kodak Theatre. It was filthy now, caked with dirt and dried blood from her father’s injuries. Her curly hair, up nicely the night before, was disheveled and unkempt. “Why are you different?” she asked with another sniffle.

I barely heard her question. Something overtook me as I stared at the image before me. Poor, lonely child, left huddling in the dark next to her father’s corpse for warmth and reassurance, with only the body of his murderer left to keep her company. How long must she have been here? How long must this setting have been her reality? Hours would have seemed like years here. Was this another new emotion I would be forced to feel? Pity?

At that moment, my brain clicked back into gear, reminding my conscious self that she’d asked a question. I felt better taking a step toward her now that she seemed more comfortable with me, so I did. I owed it to her to explain the situation, but at the same time I felt peculiar being in her presence in my current state. Sucking up my ego, I knelt down a few feet away. “I made a little mistake,” I explained, getting comfortable on the ground. I tried not to look at Matthew. His face was still swollen, blood that had dried to a stiff black color still tainted his pale skin. I didn’t have to feel for his pulse to know he was dead, had been dead about four hours or more. He looked nothing like the gentleman I saw exit the Kodak Theatre with his daughter yesterday.

Anya looked at her dad. She knew he was gone as well. I got the feeling she’d known for a while, but couldn’t find it in herself to leave him alone. “You mean killing that man?” She looked toward JD’s carcass.

I nodded a second time. “Yeah.”

“I don’t think that was a mistake at all,” she said quietly, gripping her father’s hand a little tighter. “I think that was a good thing.”

“I thought so too, at the time.” I sighed, leaning my back up against the alleyway wall. When I looked back at her I could see my comment had struck a chord of sorts. There was hurt in her eyes. Without even thinking about it, I added, “I don’t regret my decision.” I impressed even myself when I said it, simply because I didn’t think it was true. Did I just utter my first white lie? Originally, I thought so. But when I took another look at JD’s crippled form, no remorse consumed me. I didn’t regret it at all.

Book Details

About the Book

Nobody knew him. But everyone feared him.

From asphyxiation to yellow fever, Death had been the chauffer of souls for much longer than he cared to remember. Whether they were destined to Heaven or Hell, the cynical reaper had been forever responsible for the delivery of the deceased spirits. After spending all of eternity doing the same thing day in and day out with archangel Michael as his partner, Death was growing rather weary of his monotonous job. But when a chance encounter with the gifted child, Anya Smith, stirred up trouble in his routine, Death would soon find himself wishing for that comfortable monotony...

Condemned by God to live a mortal life in order to see why good people had to die, Death must quickly learn to adjust to his newly borrowed body, once belonging to a homeless man by the name of Noah Quinn. Having no experience with human emotion much less mankind's general fragility, Death must adopt Noah's alias and dodge the advances of threats both physical and supernatural, all the while trying to keep Anya safe under his care.

Betrayal, insanity, and pain both physical and mental are just the start of Noah's experiences with the living. Life among people surely holds many lessons, but Noah will soon learn more about the living than he bargained for: namely that it was a hell of a lot easier being dead than alive.

Candy Skulls provides a unique look into the mechanics of human emotion. The casual blend of dark humor and suspense creates a compelling story about the successes and flaws of mankinds' relationship with the world, and an individual's relationship with himself.

About the Author

McKenzie Maclaine is an inscrutable agnostic whose creative talents span across all types of media. She started writing at an early age and has also developed a love for hobbies such as drawing, painting, and most recently tattooing.

She currently resides with her family in Green Bay, Wisconsin.