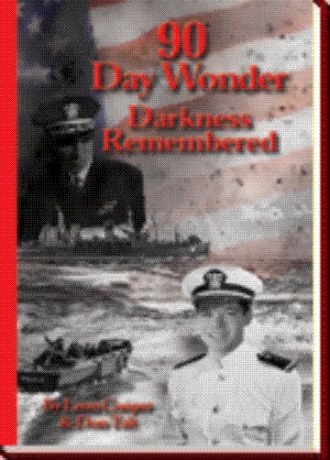

The following morning I took a taxi to the docks where my ship,

the USS Harry Lee,

was berthed. On the ride I was thinking of Alberta, of our goodnight kiss in

her room, of the goodbye kiss in the doorway. The promise to write. I think it

was more than just a platitude when she said, “Take care of yourself, Lee.”

I wanted to say “I love you,”

because I did. But I thought it was too soon.

Waiting for the elevator to come

I glanced back t o ward her door. It was ajar and she was there looking at me.

She formed a kiss and closed the door.

The taxi driver thanked me for the tip and wished me good luck and I

turned and faced the L e e. It was to be my home for thirty months. It

looked ungainly and awkward at the dock. The crew had dubbed the ship the

“Listing Lee” because she seemed to be perennially listing to port. Its

distinctive feature was a single smokestack far out of proportion to the rest

of the ship. It was difficult for me to 53 believe that the L e e had been the E x o ch o r d a, a

cruise ship that had plied the Mediterranean during the ‘20s and ‘30s. The

600-foot hull displaced 30,000 tons. She had been retrofitted to carry 20

landing craft and 1,000 troops, i n cluding a complement of 400 in the crew, or

“ship’s company.” I would have preferred a cruiser or a destroyer, but the

scuttlebutt at Midshipmans School was that destroyers and cruisers were rough

riding. Put it out of your mind, Cooper. This is what you’ve been dealt. Make

the best of it.

N e r v o u s l y, I started up

the gangplank. Arriving at the

quarterdeck I gave my business card to the Officer of the Deck, the “OOD,” as I

had been taught to do at Midshipmans School.

“What’s this?” he asked.

I was about to tell him it was to

be presented to the Captain, following school instructions, when I realized I

was about to make a damn fool of myself.

I took the card back and never used one of the 100 that had been printed

for me. The OOD motioned to a sailor to take my seabag and me to “Officers’

Country” where I would be assigned a room.

I started to follow the sailor when a voice from the navigation bridge

called down. “Are you Cooper?”

I turned and looked up at Captain

Boda who seemed to be glaring down at me.

“Yes, sir.”

“When you’re through with all

that, report to my cabin.”

“Yes, sir.”

I followed the sailor in silence.

In Captain Boda’s quarters I

stood at attention about ten feet from his desk while he signed some papers,

taking his sweet time, I thought. He put them aside and then leaned back in his

chair, finally recognizing me. Boda stared at me for a while before speaking,

checking the cut of my jib, I assumed.

“Well, well, well. Look at me,

Mother, I’m a 90 Day Wonder.”

I managed a chuckle. “I guess so,

sir.”

“Where’d you go to school,

Cooper?”

“Illinois, sir.”

“Not one of those Hahvahd Yahd

boys?”

“No sir. Middle America.”

“You don’t look big enough for

football. Did you play anything?”

“Softball. Intramural. I boxed a

little.”

Boda leapt on that. “Oh, a tough

guy, eh?” I couldn’t seem to say the right thing with this man. Again I tried

to keep it light with a chuckle. “No, sir. It was just neighborhood club stuff.

A chance to pick up 25 bucks if I won.”

Should I say that I needed the

money? No, better just answer the questions. It was difficult to determine,

with him seated, but Boda looked to be a little under six feet and about 50

pounds overweight. His features were

coarse and his nose and ears suggested he’d probably been in a few fights

himself. When he pressed his fingertips

together I didn’t see an Annapolis ring. I think Boda noticed my glance and

read my mind.

Maybe this was the kind of

reception every 90 Day Wonder got when he came aboard the Harry Lee. But it was

probably more than that. Perhaps I wasn’t quite humble enough in his

presence. Perhaps my gaze was too steady,

my bearing too proud. I did feel proud in that uniform and it must have showed.

Boda asked me a few more

questions. My answers always evoked a sardonic retort. I’d be glad to be out of

there.

He got up from his chair and in

the same motion pulled some change from his pocket. He came around to the front

of his desk and half sat on the edge of it, continuing to ask me routine

questions as he played with the coins, dropping them rhythmically from one hand

to another. Then one of the coins unexpectedly fell to the floor. I made the

slightest, almost imperceptible, move to recover it. Captain Boda stood up and looked down.

My impulse, which I had checked,

was a courtesy to a superior officer, a courtesy to my fellow man. But an instantaneous thought had stopped

me. This was no accident. It was a

test, a test to see how we were going to relate.

Captain Boda bent, picked up the

coin and returned it to his pocket. His eyes bore into me. It must have been five seconds. It felt much

longer.

“That’s all, Cooper,” he said.

As I turned to leave, I noticed

Boda just staring after me. If I had had time to think it through, I would have

picked up the damn coin. Pride be damned, I had just made a big mistake. It was

to be much bigger than I thought at the time. It would almost get me killed

more than once. I was off on the wrong

foot with Captain Boda and my life aboard the L

e e was to become a floating hell.